The Sound

I am not an expert in music, but I am a student. If you’ve never considered learning, you should. If you want to learn about theory or how to play a specific instrument, there are direct and obvious paths. You could spend an entire lifetime studying one instrument and this could be considered a worthwhile pursuit. Others become experts in musical subjects that detail the history and genre of music but never learn to play themselves, knowing intimate details about styles that lend to other styles and the artists responsible for revolutionizing the subject. They have formal courses of argument in university that have little to do with music other than its classification. Others will remain both uneducated and unaware of how to make music, play it, or know about it and still have a high opinion of what is “good music” or what deserves recognition. But none of these hit at the heart of what music is — aside from creating it. What is hard to find is information on what music does to you — how it affects you — and how we might use it as a modality for transformation.

Some of the only information out there seems to be ancient and convoluted. Some hints about 3000-year structures that have harmonious resonance and obscure purpose like the musical pillars from the Vittala Temple. Old tablets espouse the healing properties of sound but manifest as a middle-aged divorcee chanting a language she doesn’t understand and playing a singing bowl that feels more like a sound hangover than a bath. The Western approach to musical theory is staunch but lifeless. It is reduced to a guarded fraternity of symbols and notation, void of affect, avoiding the ephemeral. It identifies music by name and classification but can never tell you how or why to use it. All other systems are critical of each other, but the Western approach seems to be the most stale by not addressing the most obvious wonders about the subject. Unless you are willing to become a conspiracy theorist over the difference between 440Hz and 432Hz, there is no digestible or inspiring, readily available way to understand a subject that should have mass appeal.

The connection to music and the mystery of our universe is so awe-inspiring it is akin to taking a drug. You feel this when you play a track and it induces a sensation. You are immediately transported into a feeling, one that you will sometimes chase like a junkie, playing songs on repeat to try and understand how or why it makes you feel a certain way. “Pneuma” off of Tool’s most recent album, Fear Inoculum captivated me for almost two years. I couldn’t get over how clever the polyrhythm was or how incensed I was to learn that the guitar track took two years to write — yet guitarist, Adam Jones described it as “simple, yet satisfying.” The details of how it was made or what inspired the song might be ok for small talk but don’t explain why my heart rate is elevated or the goosebumps rising from my nape. This is what music shares with effort; the vibrations have inexplicable effects. We hold the effects as transformative qualities that can be practiced, expanded, and honed. It is simply a matter of trying to understand it.

A-U-M is a sacred sound, the holiest of acknowledgments. Purportedly it is the genesis of everything, the sound of creation. It has three distinct sounds in one expression: “aaaa-uuuuu-mmmm”. A: (अ jagrat) outward consciousness (also meaning universe). U: (उ swapna) inward consciousness. M (म् shushupti) where consciousness rests, or deep sleep. But there is also a 4th element which is possibly the most important in defining how sound affects us: silence (अनुपात्र anuttara) or pure consciousness. One would not be looked down upon for assuming it means soul or spirit and would see this concept reappear as one explores meditation and transcendental states. Silence is auspicious, without it, sound doesn’t exist.

When a sound is uninterrupted (at our level of perception) it becomes noise. Noise reduces the chances of understanding. Playing a single note at intolerable levels is considered by most peace treaties a form of torture because it drastically reduces our ability to focus. After a long enough time, it even induces delirium and psychosis.

A single note, clearly articulated by surrounding silence is not just a sound, it is a signal; a mark of communication; and in many cultural expressions, a way to cause changes in the listener. It demands attention, and when tuned appropriately, it can be a great instigator of emotion, feeling, and thought. Working in a combination of tone and rhythm, one can start to see why music is such a great asset to training, it is a soundtrack to transformation.

This 5000-year-old Sanskrit symbol captured an entire belief system, but it isn’t isolated incident. One might argue that most religions are based on sound: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” But it isn’t just liturgic, sound is at the heart of most civilizations. Confucius said that music was the most powerful instrument to moral education, fifty years and thousands of miles away from Plato, who iterated an identical sentiment. He postulated that the essence of a “thing” is sound in The Craetylus Dialogue and gave birth to the study of phonosemantics. Even if you prefer to imagine ancient man as simple and unaware of the mysteries that we can detect — but not explain — with modern scientific equipment, you can’t ignore our collective ignorance of a subject that may very well be the creation of everything.

It’s a common belief that we know more about sound today than we have in the past. Yes, we can measure and describe sound more consistently, but as a culture, we barely recognize its influence. There is a saying in African tribes that if you can talk you can sing, and if you can walk, you can dance, because the act of both is intrinsic to being part of a community. Temples in India have cymatic design features, crafted and held up by pillars that we only learned recently are three-dimensional visualizations of sound waves. In South America, songs (icaros) are woven into intricate patterns of cloth that represent ancestral prayers that date back thousands of years. The ancient Greeks designed the lyre with 7 strings to coordinate with their known planets and represented the “natural rhythms of the soul.”

Most today enjoy music as an audience for entertainment or an obligation for school credit. Specialization has taken a prominent human endeavor and isolated it to a few. It makes you ask a very difficult question, if music is so inherent to culture, why obfuscate its use? The answer is probably also very human, it is almost always used in the form of entertainment, manipulation, and propaganda — a commodity. Sound manipulation and commissioned music, were some of the first forms of mass hypnosis. The Holy Catholic Empire went to great lengths to pacify a starving population by coordinating the bright and cheerful sounds of the major scale to be played publicly. They controlled music literacy and literacy in general, condemning the use of the minor scale or other sounds associated with “imperfect intervals”. Playing something diminished or augmented was referred to as a “dissonant” sound and still is today. The tritone (augmented 4th, diminished 5th) was labeled as the “Devil’s Interval.” The ancient Chinese Yueji (record of music 206 BC) is one of the oldest and fully preserved writings on the topic. It was used to maintain order, political harmony, and security within the empire. But was also feared to be a manual for overthrowing The State. It is one of the most salient theories of music that happens to have a detailed interest on how it affects psychology.

Music is a force for union as much as it is of rebellion. It is one of the most reliable ways to speak truth to power, even if the lyrics seems to contradict its purpose. It is easy to give credit to the church for its investment into the arts, largely controlling all forms of it through the Dark Ages. Further reading on the Yueji will show that its main descriptions are of how music is used as a hierarchical ordering of the state and its people. But it is also easy to see what these regimes were investing in — control. In our lifetime, we have seen similar overreaching having to do with music, during the emergence of rock and roll sent authorities into panic, punk rock made the upper echelons of society clutch their pearls. Generation X pioneered the heavy metal uprising, and hip hop has had few artists that aren’t internationally controversial.

You won’t hear a political event, or motivational speech today that doesn’t utilize sound to help rally a group toward its cause. Good luck selling a movie that doesn’t use sound or music as the primary driver of increasing tension or revealing a villain. But what is the driver of communication? We may chant the words as a group but there is something more fundamental perhaps as simple as frequency. “Born In the USA” by Bruce Springsteen is often sung in concert to express the national pride of being American, but it is a clear criticism of what it is like to return as a Vietnam Vet and not be welcomed by the very people they risked their life for. It is an opposing theme to a common uplifted feeling. The upbeat sound and scale reflect the very same disillusionment revealed in the lyrics. It is a clever way to protest, hide an uncomfortable message in a song that delivers a distinct feeling. Another example of mixed signals was in 2000, Rage Against The Machine played for the Democratic National Convention. With a history of anti-American sentiment and anti-establishment ideals, it proves that the feeling sound gives to the masses can far outweigh the meaning in the lyrics or even the contrasted ideology of the audience. The sound of revolution seems to be obvious by repeating “FUCK YOU I WON’T DO WHAT YOU TELL ME,” but the sound itself has the notion of overturn. Played during a hard effort, reveals a similar feeling of unrest and dissatisfaction with words or absent of them. If the empires past and present attempted to harness the power of sound for control, why wouldn’t we do the same and apply what we know to ourselves?

When considering how to shape your environment with sound, you have to take time to notice how certain sounds make you feel and the difference in how they make others feel. This goes beyond “pumping the jams” or blasting 90s metal to mask any internal voice in your mental landscape. We want to enrich the internal dialogue, not drown it out. The tempo can influence states of consciousness, which means higher focus and more creativity — or neurosis. Methodical rhythms can induce transcendental states and crescendos can lead to feelings of resolution. Our cultural default is to fill the void. Elevator music to fill the space between strangers. Musak at shopping malls to mask our fear-based consumerism. Nightlife music so loud you ignore the internal signal to put down the drinks and go home.

We use music to enhance the feeling we are after. The rhythm and tone should match or complement the intention of the session. Setting the precedence for nontraditional forms of sound during training sessions gets met with great criticism when it’s not well understood — especially if you train in a group or have been conditioned to a style of socially accepted music. For this reason, I think starting with simple tones and rhythms is a good way to study how sound can shape your environment. Drones and drumming provide consistent but neutral sounds that can affect the listener beyond a simple preference. What you’ll notice is that the people who commonly complain about music or sound not being to their preference, generally have issues with silence. It’s worth asking, if sound doesn’t cause some kind of reaction —good or bad — can it change you?

Classical Music Theory of the Western tradition is difficult to grasp. I still try from time to time, but it is hard to get motivated to learn when I don’t see it helping bridge the gap to the ineffable nature that I want to understand. Because of this complexity and price of entry, I found Indian Classical Music Theory (The Ragas) to help discern what music does and how it is composed. It doesn’t make it easy but there is a map and an acknowledgment that music is doing something more than tickling the crystals in your ear. Two classifications can help you immediately use music as an outcome.

First, think of the rhthym, tempo, or (Tala). You can think of it as the speed at which a song plays, higher speed (less space between intervals) requires more intense processing from your conscious mind. People intuitively know this as they want something “upbeat” to match an intense session. As an example, alpha brainwave lengths are often found to correlate with 8-13Hz and are associated with focus. To achieve this high of a rhythm, the pattern becomes so varied that your brain seeks recognition and in doing so, focuses intently on what is in front of it. We have used this form of drumming to enhance problem-solving or high-skill development. Go too fast with the tempo and you risk kicking yourself into a state of panic or anxiety when focus cannot be achieved.

Slower rhythms (.5-4Hz) by contrast, are easily predictable and put your mind at ease, because there is no need to guess what pattern will have to emerge. You find these tempos associated with transcendental or dream-like states (Delta and Theta). They can be recognized universally as shamanic rhythms because they have been found consistently in ancient cultures with medicinal applications. This makes intuitive sense if we relate parasympathetic states (rest and digest) as being induced by these tempos. These have been shown to enhance the body’s natural recovery processes. This does not mean slow tempos need to be used for recovery, contrasted with hard efforts, they can provide insight into rates of motivation and allow more “space” for thought.

Next, think of the tone, scales, or (Swaras). To simplify, you can first think of the tone that makes you feel up or down. Is it bright or sorrowful? Start by trying to feel a precise part in your body where you “feel” a particular tone within an octave. Unfortunately, it isn’t as simple as one making you happy and one making you sad. The intonation is deeply complex. If we take the Ragas as a serious theory, it derives the reaction of each tone as a consequence of your personal energetic blockages. For instance, they posit that the vibrational characteristics align with certain spots in your body (Chakras, which translates to “wheel”). When these are free, you can channel energy up and through your body. I know most reading this won’t take this seriously, that is until you vomit profusely from the sound of a gong tuned to affect a stuck center, but it is worth considering as you play with sound and music as a way to enhance the energy you can put into a training session.

Whatever you do listen to, consider that in the most basic way, constant exposure to a sound or frequency will change your own. I have become increasingly aware of how black metal and hardcore (which I grew up loving) effect me. It isn’t that they are bad, its that they are often made with the intension of frustration and anger, which might be why they feel good when you are feeling similar, which is called resonance — a reflection and mirroring of sound waves.

These are just the most basic components to consider and are in no way a definitive guide. It is meant as an entry and direction that I don’t find “gym people” talking about. People will claim that it is pseudoscience but then they will be unable to perform when you replace their Hatebreed album with Patsy Cline. I have resisted writing anything because it is a subject that has been studied for thousands of years by countless societies and still seems quite mysterious. My hope is that this doesn’t tell you what to listen to, only to start really listening and feeling.

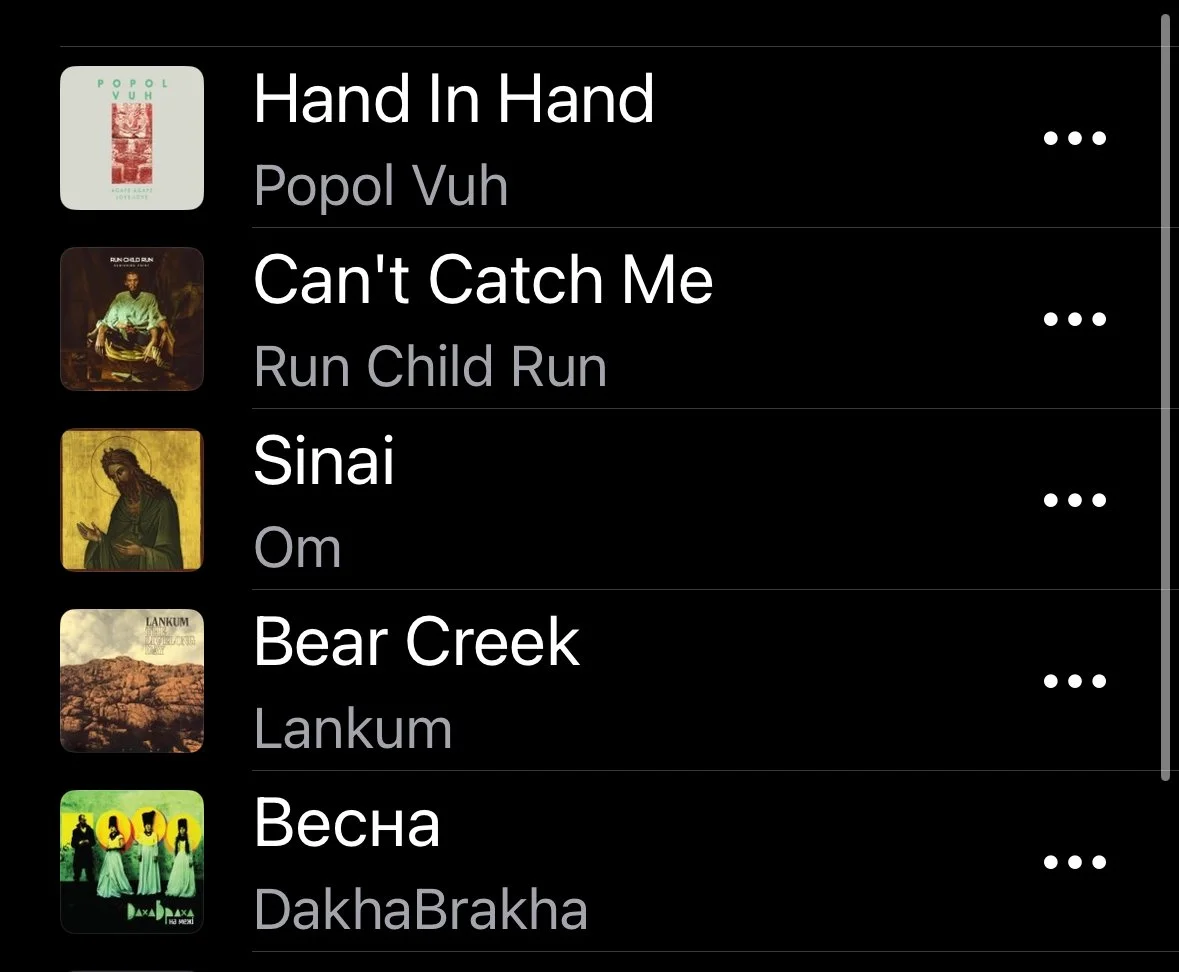

That being said, I wanted to give an example of how we might use sound. These tracks match the intention of a specific sensation apparent in an accumulation style effort; which is to say the intensity builds. This playlist has been prepared to match a session from the early days of The Space Program. It is a longer Death By series and is only meant to build pressure, not induce failure, hence the time cap. There are multiple waves of intensity as you change movements throughout, but they build again to an eventual crescendo. Each one of these songs is powerful in its own right and can alter the sensations that you experience based on where you play it and how you set the intention. I would recommend going deep, making sure that the rep scheme and movements put you as close to the edge of what is possible. Use the pressure of breathing and the waves of intensity from the music to examine parts of yourself and the desire to continue or the fear of not being able to.

Enjoy.

Apple Music :The Playlist

Spotify: The Playlist

Work:

“Assaulted Burpees”

30min Time Cap

Minute 1 - 15/12 Calories on Assault Bike

Minute 2 - Death by Burpee starting at 1 rep and increasing by 1 each time you come back to the burpees

*every 10min the style of the burpee changes but the count continues on in one format, 1, 2, 3…15

0:00-10:00 - Burpee Pull-up

10:00-20:00 - Burpee Box Jump @ 20/24

20:00-30:00 - Burpee